In a positive development towards India’s progress into a nationwide unified market and removing trade barriers in the form of cascading effects of taxation, the Central Government tabled the 122nd Constitution Amendment Bill, 2014 (‘Bill’) on the introduction of Goods and Services Tax (‘GST’) before the lower house of Parliament on December 19, 2014. This Bill replaces an earlier bill introduced in 2011 by the erstwhile government which had since lapsed.

The Bill has also been introduced on the back of hectic negotiations and parlaying between the Centre and States on various contentious issues such as taxing powers and revenue sharing, after the current government had come into power in May 2014; it is therefore significant that it has been subjected to a level of debate and concessions by the Centre and States over the past 6 months, which is key to achieving success in amending the taxing powers of the Centre and States, which is a fundamental aspect of a federal democracy like India.

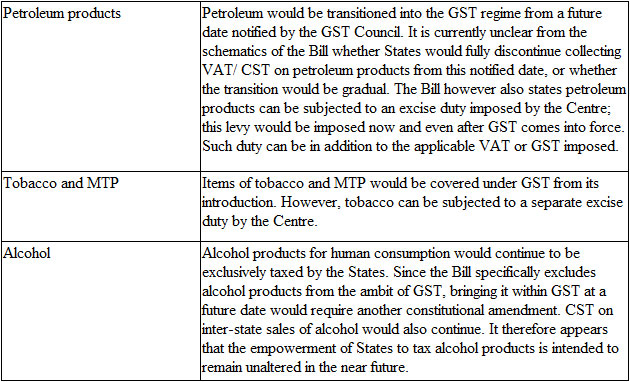

The Bill proposes to replace the current Indian tax regime which is multi-tiered. Currently, the Centre imposes excise duty on manufacture of goods, and service tax on provision of services (other than customs duty on imports). The States separately impose Value Added Tax (VAT) on the supply of goods and a portfolio of specific taxes such as entertainment tax, excise duties on alcohol for human consumption and medicinal and toilet preparations (MTP), entry tax and octroi. For mixed supply of services and goods (eg construction, restaurants), both service tax and VAT apply on the respective components. This results in a multiplicity of taxes with limited cross credits, conceptual difficulties, differential tax regimes between States and undue litigation.

In this update, we have summarized the key structural features of the proposals contained in this Bill, and how it differs from erstwhile bill introduced in 2011 along with our macro-level analysis. We have also provided a reference to the key next steps which this Bill would need to navigate through to reach fruition and our thoughts on how the industry should view this.

Key Features

- The Bill proposes that both the Centre and States would be entitled to concurrently impose GST on the supply of goods and services within a State. Effectively, every supply of goods and services would be subjected to a Central GST (CGST) and State GST (SGST) on such “intra-state” supply by the jurisdictional State.

- Entry tax imposed by various States across India when goods enter for consumption or sale within its jurisdiction. This levy has been subjected to various legal challenges in almost all States and is currently pending resolution at various appellate fora. This also posed specific logistical difficulties for the supply chain. The Bill seeks to delete the imposition of entry tax across India and is a welcome development.

BMR Analyses

This Bill differs from the erstwhile bill introduced in 2011 in various ways (summarised below) which essentially indicates a level of progress having been made on various contentious issues so as to remove the impediments to this reform.

- This Bill has managed to cover petroleum products within its ambit, albeit in a phased manner. This is a welcome development since petroleum products are key industrial inputs, and therefore should be within the ambit of GST in the long term.

(a) Resolution of disputes arising out of its recommendations

(b) Imposition of additional taxes in times of calamities and disasters

(c) Introduction of special provisions with respect to all Himalayan states in India

Conclusions

This Bill, as with any new legislation, contains transitional provisions. Such provisions allows for implementation of different provisions of the Bill at different points in time. The Central and State Governments would need to closely guard against lack of clarity and difficulties that may arise out of this; since this particular element has been criticized by the industry during recent reforms of corporate laws.

As this Bill clearly has the potential to usher in monumental changes in the indirect tax regime in India, it is only a starting point. At this stage, the current Bill is an improved and more implementable version of the one introduced in 2011, mainly due to the focus on:

- An egalitarian approach to endow the representation by States in the GST Council with wider powers; and

However, this Bill does leave certain questions unanswered. For example, the key taxing provision of Article 366(29A) which defines the various transactions of sale, lease, hire purchase, works contract etc. has been left unaltered. Since GST would be imposed on the supply of goods or services (or both), it appears that this provision could become superfluous.

It is also unclear whether the State of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) would be brought within GST. Service tax does not currently apply to J&K, and it enjoys differential powers to tax transactions within it. There is no clear indication on how J&K would be integrated into GST and its interplay with Article 370 (which provides J&K with a special constitutional status on various matters including taxation), though it is worthwhile to note that the GST Council has been empowered to make particular rules with respect to J&K as well as other Himalayan States.

While this Bill is aimed at achieving constitutional empowerment for GST, clarity is urgently needed on expected rate regime for industry to prepare for the ultimate impact; the media had recently reported a relatively high median rate of 22-27 percent while earlier indications were a notch lower. Certain administrative clarity on this issue is the need of the hour.

As evident, many of the details would be a function of the model GST legislation and its features, from norms for logistics, credit mechanism, assessments, dispute resolution, to how existing tax holidays and incentive schemes would be transitioned. Separately, the herculean tasks of setting up the requisite information technology infrastructure for administering GST on a pan-India basis as well as gearing up and training the revenue authorities at the Centre and State needs to be addressed.

As next steps, this Bill needs to be debated and voted on by the Lower House of Parliament. Thereafter, it would need to be voted on by the Upper House of Parliament, before being ratified by at least half of the States.

The wider industry should take notice of this Bill in as much to set in motion the various institutional decision makers and contribution teams to address this conceptual shift in the indirect tax regime. This change would impact almost all business divisions of industries from procurement, to manufacturing, to sales and distribution. Service providers are also likely to be substantially impacted, as they have historically been subjected to a less exacting compliance regime. It will provide the industry to take a relook at how they are organized, since:

- Almost all manufacturing companies have warehousing on a State-wise basis on account of VAT laws